The basic goal of concert recording to provide a “you were there” stereo (or surround) image in the listener’s playback system. Concert recording techniques to achieve that objective have been very well described in many sources. DPA’s Microphone University is a comprehensive source.

For the beginning concert recordist, the array of options can be confusing: should I select coincident, near-coincident, or spaced microphone pairs? Do I need more than one pair? What about using different polar patterns?

A key concept is Michael Williams’ paper on “Stereophonic Zoom“. Williams explains how microphones of various different polar patterns may be employed for any given angle of coverage by varying the angle and distance between the microphones. The late Eberhard Sengpiel provided a very nice tool for calculating stereo recording angle based on that concept. All angles given in this post are derived using Sengpiel’s tool.

There is a flash version of the SRA tool on Sengpiel’s site that has options for every polar pattern, which of course is not functional in modern browsers. It can be run in a browser extension using Ruffle.

It may thus seem very simple; all you need is a single pair of the whatever microphone you prefer (or just happen to own), and you can place yourself anywhere in a hall and derive a stereo recording angle (“SRA”) that is appropriate! Well, almost. That would be entirely true if not for these factors:

- critical distance: ambient vs. direct sound; access restrictions

- effect of time-difference vs. intensity-difference microphone techniques

- farfield frequency response of the microphone

Let’s consider each in turn.

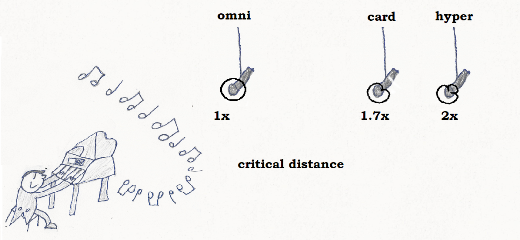

Critical distance

The critical distance is the point at which ambient and direct sound are equal. Critical distance varies according to the acoustics of the hall. While the critical distance is not the location that would usually be preferred, it is a good starting point for the novice. Once it is located, the distance may be decreased until the ambient sound is reduced to the desired balance. This can be simply done using the recordist’s (omnidirectional) ears–and feet!, and will thus discover the critical distance for an omnidirectional microphone.

For other polar patterns, the critical distance will be further from the source: 1.7x for cardioid, 2x for hypercardioid, so the according adjustment may be made. Since directional microphones have a longer critical distance, they will be preferred where the microphone placement must be further from the stage.

For discussion, hereafter in this article where the term critical distance is used, it is given a modified definition; taken to mean the location where, for an omnidirectional microphone (or ear), the recordist has achieved the desired balanced between direct and ambient sound.

Where the recordist has full access to the hall, most often they will set the recording distance based upon their choice of the microphone’s polar pattern. However, this ideal is often not realized. Due to access restrictions, the recordist may not always have the privilege of selecting the recording distance. They may be required by the venue or the artist to record from a location that is suboptimal. This will influence microphone selection, as at greater distances, more directional microphones may be indicated to due their longer critical distance.

Once you have selected the appropriate polar pattern given the desired or required recording distance, you can arrange the microphones for the SRA according to the angular size of the ensemble. To do this, the recordist must balance time and intensity differences to set the SRA.

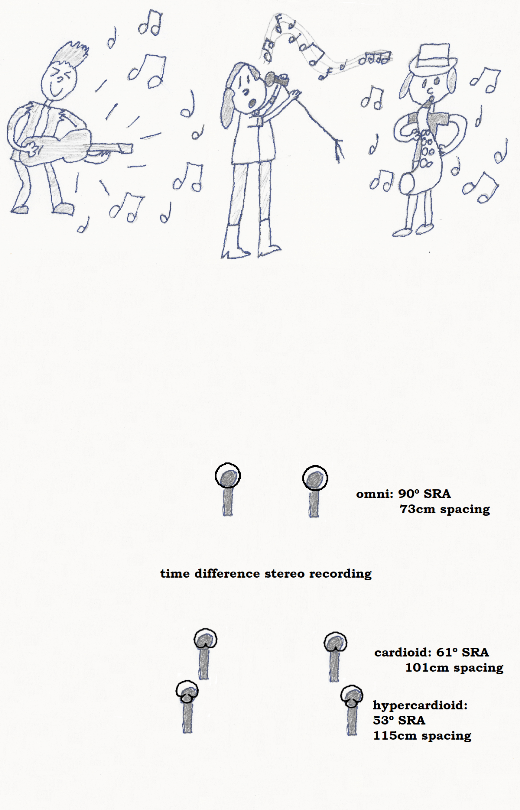

Time-difference stereo recording

Time-difference stereo uses the decrease in sound intensity over distance as a method of generating a stereo image. Sources not in the center will be closer to one microphone than the other, resulting in a louder signal in that channel. In order to generate a sufficient difference in volume purely from time differences, the distances required are typically greater than 40cm.

Let’s calculate these parameters for a recording of an ensemble in a hall. We’ll assume the stage width of the ensemble is 10m, and the critical distance (which we derive by using our ears, which are essentially omnidirectional) for an omnidirectional microphone is 5m. That yields a desired SRA of 90º, which requires a 73cm spacing.

Let’s further assume that recording distance is not accessible. Instead, a cardioid microphone could be used at 1.7x, or 8.5m, and a hypercardioid capsule at 2x, or 10m. Using a bit of trigonometry, the required SRAs are 61º and 53º, respectively. However, the critical distance factors assume that the capsules are on-axis to the source. While that can be done, the required distances increase to the point of being impractical; 101cm and 115cm, respectively.

Any of these spacings might be considered too wide for the desired stereo image, creating a psychoacoustic “hole in the middle” of the ensemble. There are techniques to address that issue, but first, let’s consider the other technique.

Intensity-difference stereo recording

Instead of relying only upon time differences between microphones in a spaced pair, it is common to take advantage of the decreasing off-axis response of directional microphones to create a level difference. Angling two directional microphones creates an intensity difference between left and right channels without any spacing of the microphones at all. This arrangement is referred to as a coincident microphone pair.

In our example, the indicated microphone angles for SRAs of 61º and 53º for a coincident pair is 240º and 151º, respectively, for cardioid and hypercardioid. Yes, for the cardioid pair, that would require the capsules be aimed away from the ensemble! Clearly, that would not yield the desired result.

Because purely coincident techniques cannot readily generate such narrow recording angles, they are often limited to close-micing applications where the desired recording is wide, such as drum overheads.

Time and intensity-difference stereo recording

Near-coincident techniques are much more common in concert recording. This combines spacing (time difference) and angling (intensity difference) the microphone pair. Spacings of up to 30cm are typically used; there are several “standards” for near-coincident techniques, often named after the organization that developed them:

“ORTF”: cardioid, 110º, 17cm — 96º SRA

“NOS”: cardioid, 90º, 30cm — 81º SRA

“DIN”: cardioid, 90º, 20cm — 101º SRA

These techniques were developed by organizations that had full control over the recording distance, so they had the liberty of developing a recording technique according to their sound preference (likely based upon the excellent concert halls they used), and then placing the microphone pair at the indicated distance for the resulting recording angle.

In our example, I have purposely forced the recording distance to be greater, because often restrictions are placed on the recordist that preclude use of standard spacings. To get our desired SRA of 61 degrees, we’d need to use a wider spacing or a greater microphone angle (“MA”). For example, a “wide ORTF” would yield a 61º SRA at a 110º MA and 41cm spacing. Or for the hypercardioid capsule at 10m, we can get a 53º SRA with a 110º MA and 30cm spacing.

There is perhaps an unintended side effect of angling the microphones: because the microphones are now off-axis to the source, they are more on-axis to ambient sound, which might degrade the direct-to-ambient sound ratio by up to 3dB. That means we may have changed the critical distance factors! So we might need to compensate by moving closer, or instead by reducing the microphone angle (to keep the source more on-axis) while increasing the spacing; yielding the same SRA, but increasing the direct to ambient sound ratio. This is the art of being a concert recordist, using our ears to listen to the change in both stereo image as well as the balance between direct and reflected sound as we alter microphone placement!

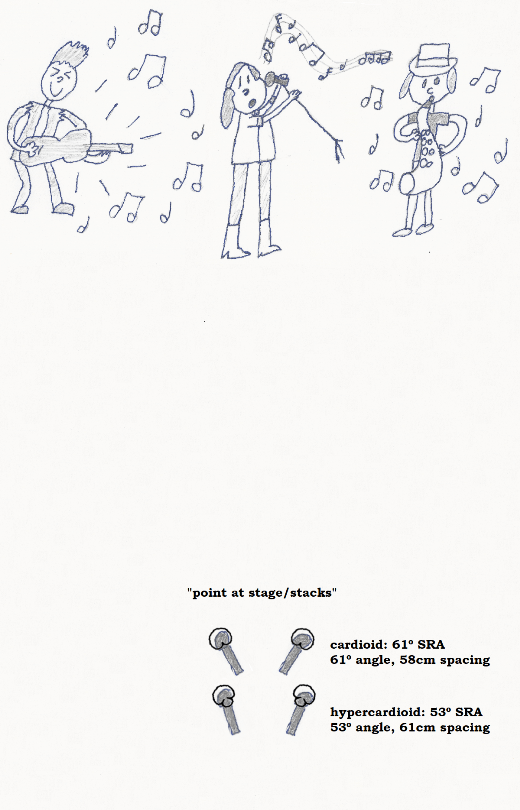

Techniques beyond the critical distance

A dedicated concert recordist at taperssection.com has made a study of the “PAS” method–no, not another organizational acronym, but rather, “point at stacks”. The rational being that off-axis sound in an amplified concert is especially undesirable, as it may contain not only reflections from the public address system, but also crowd noise! Thus, the MA is set based upon the relative angle of dual loudspeaker arrays to the recordist’s location. The same principle can be applied to an acoustic ensemble or a mixed performance, using the width of the stage as the MA, and adjusting the spacing of the microphones to make the SRA equal–or at least as close as is practical for the situation.

In our example, that results in a spacing of 58cm for the cardioid pair at 61º MA and SRA, and 61cm for the hypercardioid pair at 53º MA and SRA:

That represents the extreme edge of microphone technique–achieving a narrower SRA in a concert setting is not likely to be fruitful. At increasing distance, the stereo resolution of the direct sound may become limited, and the balance between direct and reflected sound will swing decidedly towards the ambient (or other undesired off-axis) sound. Further, the PA is probably monaural in spite of the number of stacks present, which if well designed won’t have overlapping coverage anyway!

Farfield frequency response

An important limitation in selection of polar pattern strictly on critical distance is that the frequency response of directional microphones varies by distance to the source. In the earlier article on live sound reproduction techniques, we described proximity effect, which is the increase in low-frequency response for nearfield sources. We exploited that phenomenon to increase gain-before-feedback for live sound, but for concert recording, the loss of proximity effect in the farfield is not necessarily our friend.

All directional microphones have a rolloff in low-frequency response as distance from the microphone increases. This is greater as the pattern gets more directional; it is least for subcardioid and worst for bidirectional. The rolloff also tends to occur at a higher corner frequency as the diaphragm size of the microphone decreases. That might tend to indicate use of a large diaphragm microphone, but as described in the post on microphone specifications [link], large diaphragm microphones typically have less consistent off-axis response as compared with smaller diaphragm models. This phenomenon makes large diaphragm microphones less desirable for intensity-difference stereo recording techniques, where the source will always be partially off-axis to the microphone.

So if we find ourselves in a recording situation where we are far back in a hall and thus required to use hypercardioid capsules to get the desired SRA, we are likely to have insufficient low-frequency response for a nice full-sounding recording. Or, on the other hand, some sound systems have such an excessive amount of volume from their subwoofers that this loss may be desirable!

In contrast, omnidirectional microphones have no proximity effect or farfield rolloff, and most often have a flat low-frequency response. Thus, where a natural sound is preferred, and the critical distance location for an omnidirectional microphone is accessible to the recordist, that is often the preferred choice.

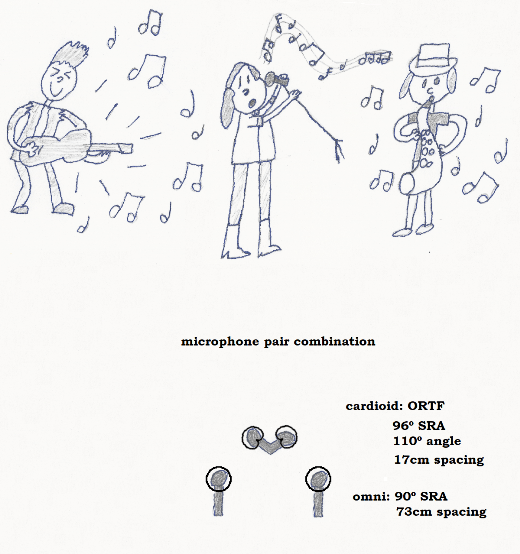

Polar pattern combinations

Recordists often employ more than one pair of microphones in order to address several of the limitations described above. For example, where a spaced pair of omnidirectional microphones are used as the main pair, a third omnidirectional microphone can be added as a center mic to avoid the “hole in the middle” problem. The spacing of the main pair can thus be further increased to enhance the perceived “spaciousness” of the recording, especially at low frequencies.

This technique was pioneered by Decca; the “Decca tree” uses three omnidirectional microphones with the center microphone advanced in front of the spaced outer pair. The Decca tree had a further innovation; the Neumann M50 microphones used had its capsules mounted in spheres. The spheres created a directional high-frequency response, which narrows the apparent SRA at a given microphone spacing. It also makes the off-axis ambient sound less bright by comparison, which is generally a pleasant effect. Some recordists substitute a directional coincident or even near-coincident pair for the center omnidirectional microphone.

The same concept can be applied where the near-coincident pair is considered as the main pair: adding a pair of spaced omnidirectional microphones can restore the low-frequency response that the directional main pair lacks, and the de-correlated ambient response of the omnidirectional pair can add a pleasant spaciousness. The directional main pair can be placed closer than the critical distance to maintain the integrity of its stereo image. To preserve the precision of the stereo image of the main pair, the omnidirectional spaced pair can be low-passed as required; anywhere from 100Hz to 3kHz might be desired as the corner frequency.

Baffled stereo recording techniques

Another technique is the use of a baffle to create (for an omnidirectional microphone) or increase (for a directional microphone) the intensity difference between a microphone pair by absorbing sound incident from the opposite side. You might have been wondering why, in the first example, the indicated spacing of our omnidirectional pair was 73cm, when our ears are quite a bit closer together than that! The answer is partially because of the baffle effect from our head, and also because our brain doesn’t mind a wider SRA in a live concert than it will accept on stereo playback.

The most popular baffled technique is binaural recording; that is, where an omnidirectional pair is placed directly at or in the ears of a human or mannequin head. It yields an incredibly lifelike stereo image on headphones; the effect is somewhat less convincing on speakers. Other baffled techniques include the Jecklin disc and its variants.

The major disadvantage of baffles is that their effect varies by frequency according to the size of the baffle—which is also a limit on how widely the microphones can be spaced. Also, in some environments, a baffle may be visually unacceptable. And of course if you are using your head as the baffle, you have to be careful not to move or cough!

Naiant solutions for concert recording

The X-R microphone series and accessories are designed especially with the goal of solving nonstandard concert recording situations; whether due to restricted access, limited power availability, or a requirement for minimal visibility of the microphone.

The X-R system offers a wide range of capsules, including three polar patterns (omnidirectional, cardioid, and hypercardioid).

Naiant has three single-microphone-stand stereo recording solutions:

- The X-R stereo bar can mount up to six capsules on a bar up to 120cm length. The capsules can be powered by either the X-R remote amplifier or up to four capsules with the X-R quad microphone amplifier.

- The X-8S stereo/multipattern microphone can be used as a coincident stereo pair with SRA of 95º, or in bidirectional mode, together with the X-R remote microphone and mid/side mount accessory, offering mid-side recording with SRAs of 180º and for cardioid and 129º for hypercardioid center capsules.

- The X-R interchangeable capsule amplifier can support from one to four capsules in mono, stereo, three, or four channel configurations. The X-R system offers a range of fixed or interchangeable stereo capsule heads, including 90 and 120 degree angle options, three capsule (for encoding to mid-side or remote extension for Decca Tree), as well as four capsule heads for two-pair stereo or surround solutions. With or without the RCA Y-adaptor, the X-R system can generate a wide range of SRAs from 80º to 140º with direct-mounted capsules:

| Spacing/ Stereo Recording angle |

Capsule on head | Coincident with RA adaptor |

Coincident with Y adaptor |

With Y adaptor | With male & female adaptors |

| 90º, standard capsule | 8cm card: 147º hyper: 92º |

3cm card: 177º hyper: 103º |

0cm card: 180º hyper: 109º |

13cm card: 124º hyper: 83º omni*: 180º |

15cm card: 117º hyper: 80º omni*: 165º |

| 120º, standard capsule | 9cm card: 114º hyper: 67º |

N/A | N/A | 16cm card: 93º hyper: 59º omni*: 127º |

19cm card: 86º hyper: 57º omni*: 114º |

| 180º, standard capsule | 11cm card: 73º hyper: 27º omni*: 123º |

N/A | N/A | 19cm card: 62º hyper: 25º omni*: 91º |

22cm card: 58º hyper: 25º omni*: 84º |

| 90º, short capsule | 6cm card: 158º |

0cm card: 180º |

1cm card: 180º |

12cm card: 128º |

14cm card: 120º |

| 120º, short capsule | 7cm card: 122º |

N/A | N/A | 14cm card: 98º |

17cm card: 91º |

| 180º, short capsule | 9cm card: 77º |

N/A | N/A | 17cm card: 64º |

20cm card: 61º |

*OMNIDIRECTIONAL CAPSULE EQUALIZATION DISC

Thus, a single X-R microphone can be used for any stereo recording technique. Several X-R system accessories enhance stereo recording possibilities:

- The RCA Y-adaptor can also be used to mix two capsules into a single input. This can be used to blend capsule patterns; for example, the nearfield cardioid and omnidirectional capsules to yield a subcardioid capsule.

- The acoustic lowpass filter can be added to that configuration. With that accessory, the omnidirectional capsule can “fill in” the bass response of a directional capsule, such as the nearfield cardioid or hypercardioid, without affecting the stereo image of the directional pair.

- The equalization disc for the omnidirectional capsule creates an on-axis high-frequency boost, as with the microphones used in the original Decca tree system.

Finally, the X-X microphone offers the lowest noise capsule for binaural recording in its class, which may alternatively be mounted on a stereo bar.